Image © Jonny Matthew 2024 (Made with DALL-E)

If you’re a free subscriber to Jonny’s Substack and would like to support the work please consider becoming as a paying subscriber (it’s only a fiver)…

Introduction

One of my constant refrains when training is to encourage colleagues to read.

I am, and always have been a passionate believer in the need to stay teachable, hold our practice in an open hand, remaining adaptable and willing to change as we learn.

While I love reading about ADHD, youth justice, recovery from trauma and the brain particularly, I’m mindful that these are quite specific areas of practice. Underlying all these areas of work and the systems in which they sit, is theory.

This series of posts will attempt to summarise theories relevant to anyone in professional practice with troubled children and their families. I’ll focus-to start with at least-on broad theories of child development.

We’re starting with Bronfenbrenner because he came up in conversation with a colleague this week. I know, sorry if you thought I was more considered than that, but…

Here goes!

Ecological systems theory

Child development is a complex and multi-faceted process influenced by a variety of factors, both internal and external. One way of understanding these influences is Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory.

Developed in the 1970s, this theory has since become a cornerstone of developmental psychology and social work, helping professionals understand how different environmental factors interact to shape a child’s growth and behaviour.

In this post, we’ll explore the key components of Bronfenbrenner’s theory and discuss its practical implications for those working with children, particularly those who have experienced trauma or abuse.

***…in order to understand human development, one must consider the entire ecological system in which the growth occurs. (**Bronfenbrenner, 1994)

The Basics of Ecological Systems Theory

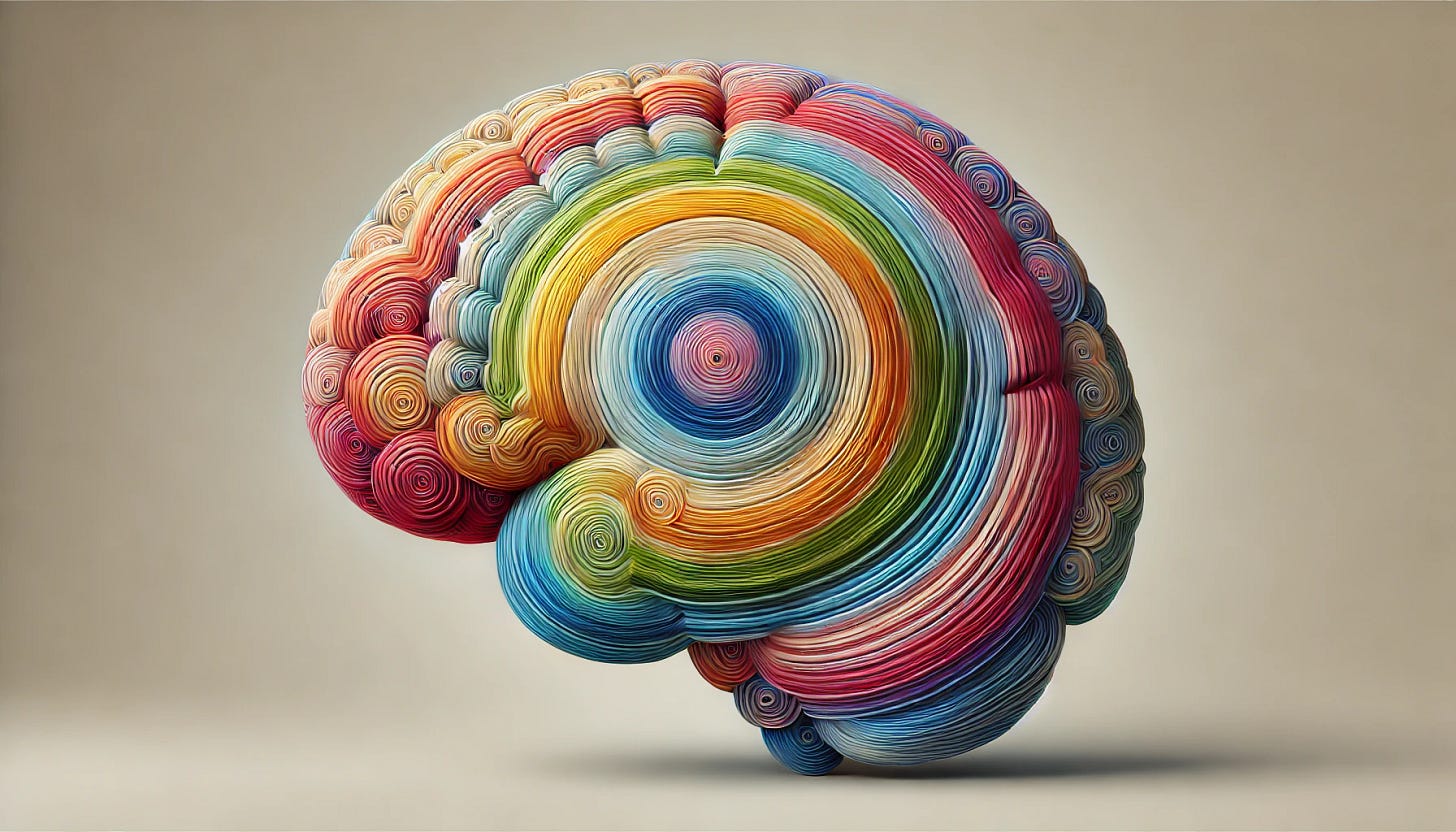

Bronfenbrenner’s theory posits that a child’s development is influenced by various systems of their environment, which interact with each other. Bronfenbrenner describes these systems as ‘nested structures, each inside the other like a set of Russian dolls.’*

They are most often depicted as a set of concentric circles moving out incrementally around the child, each influencing their development in unique ways.

Image © Courtesy Rotel Project

Five primary systems:

Microsystem:

This is the innermost system, the one closest to the child and includes their immediate environment, such as family, school and peer groups. It’s where the most proximal interactions occur. For example, a child’s relationship with their parents, teachers or friends directly affects their development.

Mesosystem:

This layer represents the interactions between the different parts of the microsystem. For example, the relationship between a child’s parents and their teachers or between the family and the child’s peer group. When these elements interact positively, they create a supportive network that promotes the child’s well-being.

Exosystem:

The exosystem includes broader societal and community systems that indirectly impact the child, even though at least one of them does not directly involve them. For example, a parent’s workplace, a church or other religious or social group or extended family members. For instance, if a parent is stressed due to a demanding job, this can indirectly affect the child’s emotional environment in the family home.

Macrosystem:

This encompasses the wider cultural and societal context in which a child develops. It includes cultural values, laws, community, social or ethnic/religious norms. For example, societal attitudes towards education, gender roles or mental health can influence how a child is parented and what opportunities are available to them growing up.

Chronosystem:

This dimension adds the element of time, reflecting the changes and transitions that occur in a child’s life, such as parental divorce, oscillations in family wealth/poverty, moving to a new town, political changes or the broader historical context like economic recessions or technological advancements. These changes can have significant, long-lasting effects on a child’s growth and development.

Application: Putting theory into practice

Understanding Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory can help the full range of child care professionals develop a holistic approach to working with children, especially those who have experienced trauma or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

Here’re some thoughts on how the theory can inform practice:

1. Holistic Assessment and Intervention

Consider Multiple Influences: When assessing a child’s situation, it’s essential to consider all the systems in play. A child’s behaviour can’t understood in isolation; professionals need to look at the family dynamics (microsystem), school environment (mesosystem), and broader societal influences (macrosystem). Noting how these have changed over time (chronosystem) can be useful, too.

Tailored Interventions: Interventions should be designed to address issues across different systems. For example, if a child is struggling in school due to bullying, a social worker might need to work with the family to improve home support, collaborate with the school to address bullying policies, the youth justice or youth work team for some prevention work with the protagonist and perhaps connect the family with community resources (exosystem) for additional support.

2. Strengthening the Microsystem

Family Support: Strengthening the family unit is often crucial. This system is the most immediate, the most influential-particularly in the early years- and the most invested. Action here might involve providing parenting support, improving communication within the family or addressing /supporting any domestic issues that might be impacting the child.

School Collaboration: Engaging with schools can help to ensure they are aware of the child’s needs, can take account of the challenges the child faces during the day and are equipped to support them. Creating a positive school environment can act as a protective factor against a whole range of adversities. For kids living in less stable environments or dealing with parenting inconsistencies, school is often the principal stabilising factor in their lives; as such, recognising and bolstering this ‘system’ can be transformational.

3. Building Effective Mesosystem Connections

Facilitating Communication: Encourage and facilitate communication between different parts of the child’s microsystem, such as between parents and teachers or social workers and healthcare providers (mesosystem). Coordinated support networks are more effective than isolated efforts; so again, recognising and strengthening interactions between these systems can help ‘hold’ or ‘contain’ the developing child more effectively.

Promoting Consistency: Ensure that different support systems provide consistent messages and interventions. For example, if a child is receiving therapy, ensuring that parents and teachers are also aware of the therapy goals can help reinforce positive changes. Feedback loops between the different aspects of the child’s microsystem, can smooth the way for interventions to gain traction and take effect. It is often child-centred professionals who can most effectively take on this inter-agency advocacy role.

4. Addressing Exosystem Factors

Supporting Parents and Caregivers: This involves recognising the stressors that parents and carers may be under, such as unemployment or mental health issues, which can impact their ability to care for the child. Encouraging and enabling parents and other key adults to proactively understand and foster links between the systems influencing them and the knock-on effect on the child, helps them see and think systemically. In turn, they can be more settled, freeing up emotional resources to parent more effectively. Providing resources and support for the adults in the child’s life is crucial.

Community Resources: Connect families with community resources such as counselling, charitable services, financial assistance/benefits, peer or professional support groups or educational programs. The availability and accessibility of these resources can significantly influence a child’s development by influencing the people closest to and most influential in setting the child’s immediate environment (microsystem).

5. Considering Macrosystem Influences

Cultural Sensitivity: Being aware of the cultural background of the child and family, respecting and integrating values and beliefs into your work can make assessments more thorough and insightful and interventions better targeted, more effective and more acceptable to the family. Constantly developing our own knowledge and awareness of minoritised groups and staying mindful of our own confirmation bias can help us avoid bad habits in the work.

Advocacy: Engage in advocacy work to influence policies that impact children and families. Frontline professionals have valuable insights to offer those making policy further up the agency, local authority, charity or private sector food chains. Both our own views, forged in the crucible of everyday practice, and the views of the children themselves as we represent them to others, can lend a powerful influence to ongoing policy development and even legislation. This might involve working towards more equitable educational opportunities, better mental health services, more targeted intervention options or policies that support work-life balance for parents, to name but a few.

6. Responding to the Chronosystem

Supporting Transitions: Be especially attentive to significant changes in the child’s life, such as moving homes, changes in family structure or entering adolescence. One to the most recurrent and poorly handled of these in my working world, is when teenagers transition to adult services - whether it be in the criminal justice, social work or mental health systems. The other is when young people leave a custodial or other secure setting. These transitions can be times of hugely elevated vulnerability and require tons of planning and additional support.

Long-Term Perspective: Understand that the effects of trauma or adverse experiences may not be immediate. Some challenges may emerge or evolve over time, requiring ongoing monitoring and support. I’ve noted many times over the years that children sexually abused in their younger years may not show any outward signs (and therefore receive no treatment or other help) until they reach adolescence; becoming a sexual being at puberty sometimes precipitates the need to finally deal with old wounds. Taking the longer view and remaining mindful of the later impact of early stressors can help children navigate the blips and hiccups they experience along the way and stay on course.

Final thoughts

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a pretty comprehensive framework for understanding the various influences on a child’s development.

By recognising that a child’s behaviour and well-being are shaped by multiple, interacting systems, child care professionals can adopt a more holistic and effective approach to supporting children and families. Whether through direct support, strengthening families, community engagement or advocacy, applying this theory can help create a more supportive environment for children to grow, heal, and thrive.

Is there any other way?

See you in the next one!

More information

PAPER: *Ecological Models of Human Development - Urie Bronfenbrenner (link)

PAPER: For an ecological look at youth justice see Diana Johns et al’s paper (download link)

Subscribe & Follow?

You can join Jonny’s mailing list here. Your information is safe and you can unsubscribe anytime very easily.

If you want these posts sent straight to your inbox, click the blue subscribe button below.

You can also “Like” this site on Facebook and “Follow” on Twitter, Pinterest or connect with me on LinkedIn.

©️ Jonny Matthew 2024